Last time, I discussed a couple different types of cash flow and offered up the idea that some are more appropriate than others when analyzing a target’s true cash flow.

I’ve previously discussed (and differentiated) the two important theoretical business entity values – Equity Value and Enterprise Value.

Recall that we’re working towards completing the following equation:

Value ÷ Cash Flow = Multiple of Cash Flow

Now, it’s finally time to divide the two to derive Multiple of Cash Flow, a highly useful metric for comparison and valuation purposes. But the question is: Which Value to divide by which Cash Flow?

The Matching Principle

Enter the Matching Principle. The Matching Principle in valuation is the principle of matching capital structure-appropriate cash flow with likewise capital structure-appropriate theoretical entity value. In other words, only divide Enterprise Values by unlevered cash flows and only divide Equity Values by levered cash flows.

Okay. Makes sense.

The reason for this, which is hopefully clear from my proceeding posts, is because Enterprise Value is a theoretical capital-neutral value that can only be derived via unlevered flows (cash that is available to all capital providers). Conversely, Equity Value is the residual ownership value of a company — after all capital providers have been paid and/or reimbursed. Equity Value can only be derived via levered flows that take into account the entire (including debt) capital structure.

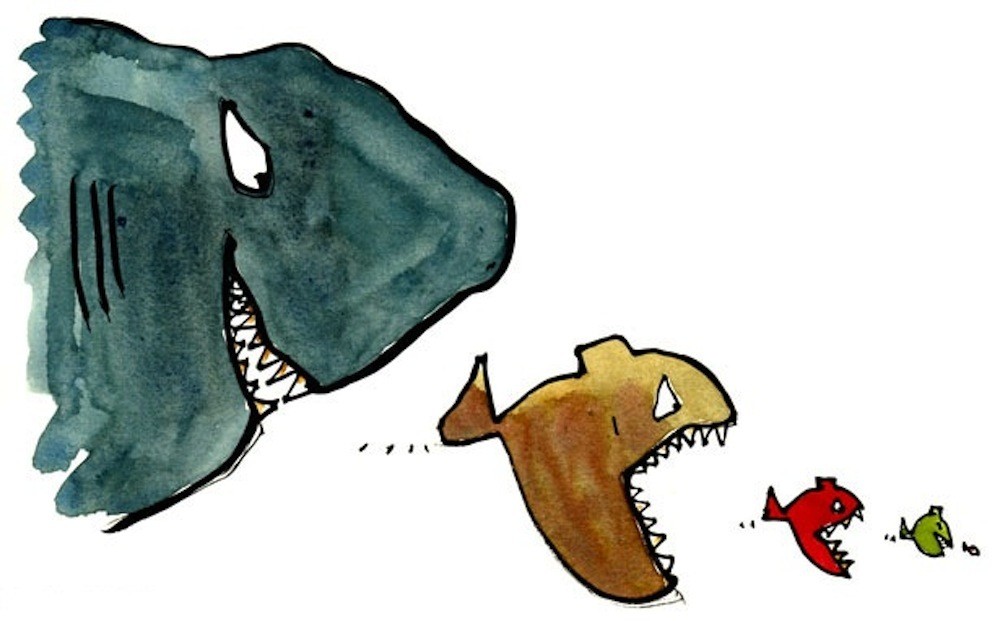

In real world corporate M&A (and private equity), everyone cares much more about enterprise value-based multiples than equity value-based multiples:

First, all owners are affected by capital structure, even if they have nothing to do with the debt or the debt investors directly. If a company were to go bankrupt, the debt investors would have the first claim to all the company’s assets.

Second, accurate Equity Value-based multiples are very hard to derive. Things become problematic when you consider private company equity, differing tax rates, non-cash charges, etc.

By using Enterprise Value-based multiples such as Enterprise Value/UFCF and Enterprise Value/EBITDA instead, you obtain a more normalized view of how a company is performing, excluding tax rates, interest, and non-cash charges. And you can always derive an Equity Value-based valuation by later moving from Enterprise to Equity Value (like I’ve described here, but in reverse); this is a very useful approach for valuing private companies.

I would argue that this method of cash flow multiple valuation is the easiest, most practiced, and very possibly the best valuation methodology in use today in real world corporate M&A. Sure, there are other methods and other metrics — DCF and its advocates instantly come to mind — but isn’t it comforting to dig in and understand cash flow and then simply figure out how many times over you’re willing to pay for it?

Posted by: Mory Watkins