Last time, I went over how to choose comparable companies and transactions to make a relative valuation of a target company. Today, I want to make a couple points about interpreting and drawing reliable conclusions from that comparable data.

Here goes…

Suppose your comparable data indicates that the market values similar companies at an average Enterprise Value/EBITDA multiple of 5x, but your target company, a small public company, has a higher Enterprise Value/EBITDA multiple, of say 10x. Is your target over valued? Is the target a “better” company than its apparent peers?

Well, the difference in multiple may be for a reason as simple as the target is less profitable than the comps. If the target has lower profitability, for example an EBITDA/Revenue of 5% compared to an EBITDA/Revenue of 10% for the comps data set, the enterprise value multiple will be higher, all other things being equal. I raise this issue because people usually think, “Higher EBITDA multiple = better”, but that is not always true – it might only mean that the target company’s EBITDA margin is lower. And if you are noticing significantly different growth rates and margins between your target and your data set, they might not be that comparable in the first place. Lesson: Verify business models are similar and look closely at margins when picking comparables.

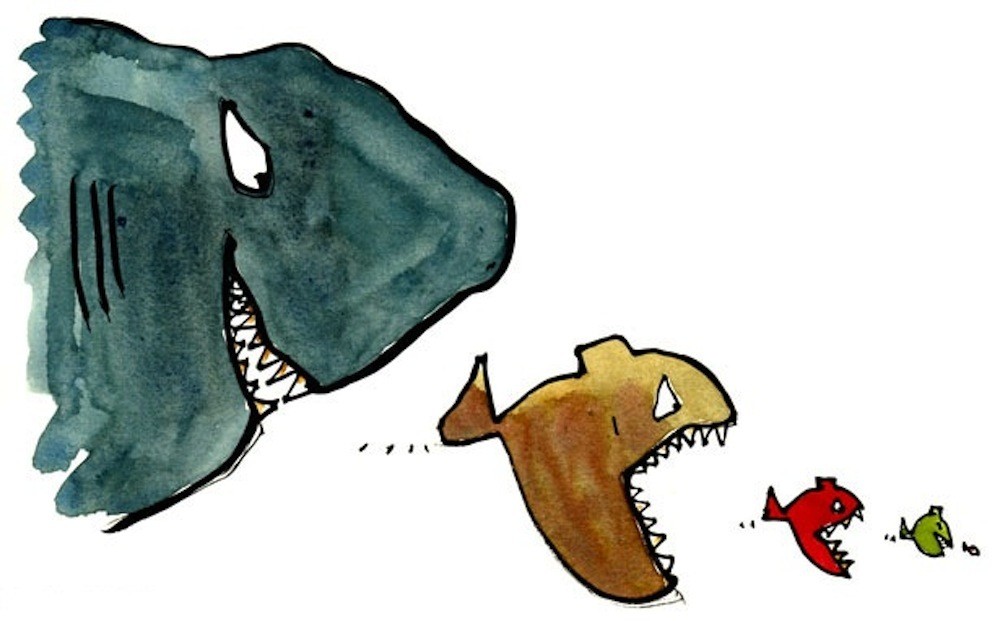

Suppose that in order to pick good comparables you must select companies that have vastly greater (or smaller) enterprise value than your target. Is this a problem?

The short answer is…not necessarily. While size is an important metric in comparability, relative valuation and the process of examining multiples handle this issue rather nicely. Absolute equity or enterprise values, in themselves, really don’t say anything about the valuation of the company. Size is just size. You must examine multiples because, really, what you are seeking is the market’s assessment of value relative to revenue, cash flow, profit, or whatever other metrics you choose. Lesson: Don’t be overly concerned with size. It’s much more important to look at multiples in relation to financial performance.

Suppose you’ve selected good comparable companies, and the financial performance and margins are largely the same between your target and the comparable companies data set, but your target, a small public company, is valued markedly higher than it “should be” by the market. What could explain the higher market value and what are the implications?

I’ll address this one by first revisiting what I consider to be one of the most important tenets of corporate M&A — always analyze and buy trailing performance. As I say here in Part Two of my Successful Corporate M&A best practices posting, it is critical to maintain focus on pricing deals as a multiple of trailing cash flows and not be distracted by notions of paying for projected performance. In my opinion, the purchase price should always be set (or at least considered) as a multiple of trailing cash flow.

Returning to the problem, if trailing financial performance shows that the target and the comparables are about the same, the only logical reason for a large deviation in value must lie in future growth prospects. If the answer isn’t in the past, it must be in the future. Here, I’d advise i) exercising a healthy dose of caution, and ii) becoming a lot more familiar with and comparing/contrasting the growth prospects of the comps and the target. A quick and easy way to do this is simply by pulling some equity research reports. Lesson: Use extra caution when deviating from the tried and true corporate M&A practice of purchasing trailing performance.

Next time — a high level overview of M&A transaction modeling.

Posted by: Mory Watkins