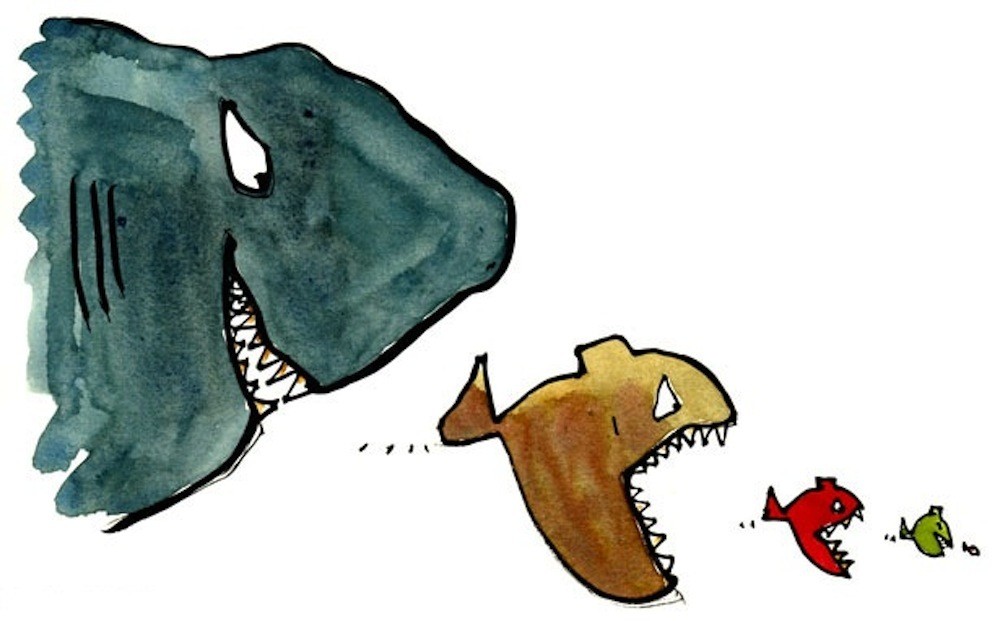

Someone a lot smarter than me once said that there are only 3 ways to make money in roll-ups – improve your margins, use leverage, and arbitrage the difference between private and public markets. Today, I’m going to delve a bit into the first roll-up value creating strategy: improving margins.

I worked for a pretty conspicuous roll-up of a B2B distribution vertical. We started as a so-called “poof” roll-up, and then grew at one of the fastest rates in US business history, joining the Fortune 500 from nothing just three years from start-up. We achieved this amazing growth by buying literally hundreds of smaller and mom & pop companies. Practically overnight, we gained a dominant market share position and “assembled” a company worth billions out of all those acquisitions. Along the way, we also helped bring roll-ups into vogue as a business strategy, and we revolutionized the way roll-up methodology is now applied to highly fragmented industries. In short, nobody previously had ever bought so many smaller companies so quickly.

The real magic, and the secret to our success (in my opinion), was our message. It was particularly cogent. The communication of our strategy was persuasive to our sellers, compelling them to let us buy them, and it made intuitive sense to our investors, who provided us plenty of capital to execute our roll-up strategy. We did a great job of getting across to the market the benefits of joining together.

This was essentially our message: We will begin to double the profitability of the companies we buy from day one — a pretty bold statement. You might fairly ask, “How were you able to do that?” The answer: via in-the-bag efficiencies and cost savings. You see, the average target company in our niche had about 5% cash flow (that is, the ratio of trailing, adjusted cash flow to revenues was usually about 5% or 500 basis points). Admittedly, not too exciting profitability. But, as buyers, we brought a couple important things to the table:

- More Buying Power: Purchasing discounts we negotiated from our suppliers due to our sales volume typically would lower the COGS of our acquisitions at least 400 basis points in terms of cash flow. Buying better makes a huge difference for a small company.

- Lowered Facilities Cost: By using a nationwide hub-and-spoke system, most of our acquisitions were able to give up or share a warehouse or some other facility with a nearby sister company under our umbrella. The savings from facilities were less immediate, but they were very certain. The savings could reasonably be expected to average around 300 basis points in terms of cash flow, ceteris paribus, when all was said and done.

- Lower Administrative Costs: As a multi-billion dollar public company, we were able to negotiate better rates from providers for everything from long distance to insurance. The collective savings in administrative costs were typically at least 200 basis points in terms of cash flow.

- More Products/More Customers: Most of our acquired companies experienced an immediate boost in sales as a result of now selling more products, carrying more SKUs, and getting more sales leads and cross-selling opportunities as a result of becoming part of a larger company. The immediate, collective revenue boost from these factors was typically at least 100 basis points in terms of cash flow.

There you have it – a full 1,000 basis points improvement in the cash flow/revenues ratio (and those aren’t even all the savings/improvements we promised). We told our sellers and investors that if we were even half right, we would still double the profitability of the companies we bought…and it was true.

And how much value did we create doing these acquisitions? Well, add up all the newly acquired and newly created cash flow and then multiply it times the private market (target) and public market (acquirer) differential. Answer: a lot. And a pretty nifty arbitrage, to say the least.

Posted by: Mory Watkins

Today, a brief posting about shortcuts and practical rules of thumb for figuring out whether a prospective transaction might be accretive or not.

Today, a brief posting about shortcuts and practical rules of thumb for figuring out whether a prospective transaction might be accretive or not.

Today I’m going to go into more detail about how P&Ls are combined in mergers — and how it’s analyzed in “real world” corporate M&A. As I’ve already mentioned, how the P&Ls come together, and what the resulting accretion or dilution will be, drives strategic M&A more than any other factor. It’s appropriate to drill down now and get more specific about what the combined income statement will look like.

Today I’m going to go into more detail about how P&Ls are combined in mergers — and how it’s analyzed in “real world” corporate M&A. As I’ve already mentioned, how the P&Ls come together, and what the resulting accretion or dilution will be, drives strategic M&A more than any other factor. It’s appropriate to drill down now and get more specific about what the combined income statement will look like.