In case you missed it, there has recently been some uber-interesting valuation discourse around the blogosphere regarding Uber, the company whose smart phone app connects drivers with those wanting rides. The buzz is about Uber’s pre-money valuation, $17 billion, implicit in its latest round of financing. It all seems, shall we say, a bit aggressive for a company with an estimated $300 million in annual revenue and little if any operating income.

Most prominently in the skeptics’ corner is Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at NYU, who recently published a detailed analysis and valuation that trimmed the Uber valuation down by about 2/3rds to $5.9 billion.

Most prominently in the advocates’ corner is a Series A investor and current board member of the company named Bill Gurley. Gurley posits an eloquent defense that Damodaran’s numbers are off by a country mile factor of 25 times and that, as the latest group of investors has freely determined, the company is worth every penny of its $17 billion valuation if not more.

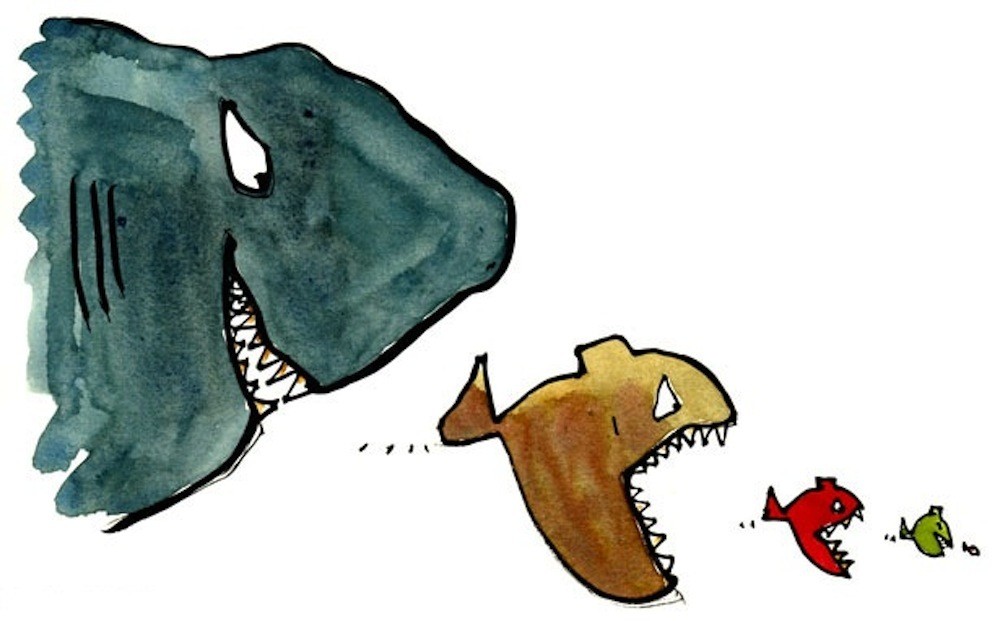

There’s tons of interesting stuff and debatable points in both of these analyses (the impending doom of the world’s “car ownership culture”?!?), but, to me, the heart of the issue is something both gentlemen are calling “disruption” aka category-killing. Effectively, Gurley says that Damodaran is missing the boat because he doesn’t understand that Uber is in the process of killing off multiple categories at once and, because of this, the TAM (Total Available Market) is bigger, by orders of magnitude, than Damodaran has considered. Check out this little historical I-told-you-so gem cited by Gurley:

“In 1980, McKinsey & Company was commissioned by AT&T (whose Bell Labs had invented cellular telephony) to forecast cell phone penetration in the U.S. by 2000. The consultant’s prediction, 900,000 subscribers, was less than 1% of the actual figure, 109 Million. Based on this legendary mistake, AT&T decided there was not much future to these toys. A decade later, to rejoin the cellular market, AT&T had to acquire McCaw Cellular for $12.6 Billion. By 2011, the number of subscribers worldwide had surpassed 5 Billion and cellular communication had become an unprecedented technological revolution.”

Damodaran, for his part, says the divergence between his narrative and Bill Gurley’s lies broadly in how their valuations address the “probable”, the “plausible”, and, for good measure, the “possible”.

So where do I stand on Uber’s valuation? I confess to a certain amount of fence-straddling in this particular situation. I know and expect that there are measures of both art and science in any valuation. I stand with Damodaran in trying to factually dissect and understand what is driving this frothy valuation. I stand with Gurley in promulgating huge, radical ideas that break down barriers and ultimately change the world. The verdict awaits.

Posted by: Mory Watkins