As I’ve said before, taxes and tax attributes play a major role in M&A negotiations. Recall that, unfortunately, deal structuring is usually a zero-sum game, and a deal structure that favors one party tax-wise is usually to the other party’s detriment. An easy way to consider the tax consequences of different deal structures is to use a simplified inside/outside tax basis framework.

First though, a small refresher on tax basis and gains. The tax basis of assets is usually analogous to the book or accounting value of assets except where it has diverged over time due to depreciation or amortization methodologies. A gain occurs on the difference between the purchase price and the tax basis (a loss occurs if the tax basis exceeds the purchase price). Lots of additional factors effect the size and nature of a gain – ordinary or capital gain, the tax status of seller, holding period, tax rate, etc.

Now to the inside versus outside tax basis framework. Inside basis refers to the basis a company has in its own assets. Outside basis is the basis that a shareholder has in the shares of another company. Deal structure will dictate how the inside and outside gains or losses occur.

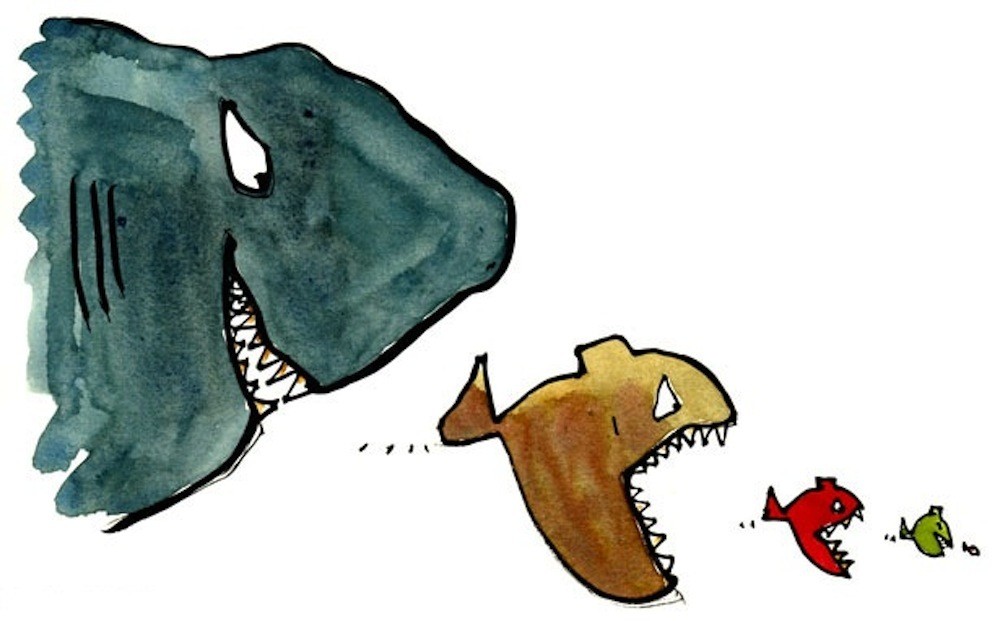

Deals are structured as either asset or stock deals:

- In a taxable asset deal, the seller is taxed on its inside asset basis and its shareholders are taxed on the gains of these sales proceeds. This is two levels of tax. The purchaser of the assets acquires a stepped up (fair value) basis in the assets and the new, greater depreciation and amortization are tax deductible.

- In a taxable stock deal, seller shareholders are taxed on their outside basis in the seller’s stock (only); there is no tax liability incurred in connection with the assets. This is one level of tax. The purchaser gets a stepped up (fair value) basis in the stock and a carry-over basis in the assets.

That’s it. There is a special case to be considered when the acquisition target is a corporate subsidiary and is at least 80% owned by its parent. In this case, the target can sell assets and distribute their proceeds to the parent shareholders without actually incurring a 2nd layer of tax (because, technically, the distribution of proceeds should qualify as a tax-free liquidation). In deals like this, the main consideration is the difference between inside and outside bases.

Also, there are several tax-free structures where the major determinant is the form of consideration paid by the buyer (cash or stock) rather than the structure (asset or stock). Essentially, if around 50% of the purchase price is paid in stock of the purchaser the deal may be tax-free because deals that use an abundance of buyer stock can qualify as “reorganizations”.

For a more detailed approach to tax repercussions of different deal structures, go to my prior blog posting here.

Deals are often scuttled due to tax considerations and, more specifically, failure to account for a deal structure’s impact on the sellers’ after tax proceeds. Understand the inside/outside tax bases, analyze, and win more deals.

Posted by: Mory Watkins