Large financial decisions are the purview of Boards of Directors, and few business decisions are bigger (or have more repercussions) than corporate acquisitions and divestitures. Today’s BODs want to be kept apprised of all material strategic developments, and want more information and more frequent updates than ever before. Considering that 93% of all acquisitions valued over $100 million now result in litigation, I can’t say I blame them.

Today, I’m going to share some thoughts about the interaction between BODs and their corporate dealmakers.

Before I begin, it’d be helpful to first understand a little bit about how BODs work. Boards walk a fine line between protecting and growing corporate assets, and they have a legal duty called the duty of care to make decisions about M&A on behalf of their companies that are “reasonably informed, in good faith and rational judgment, without the presence of a conflict of interest.” The words reasonably informed are key, and the BOD takes this part of its duty especially seriously.

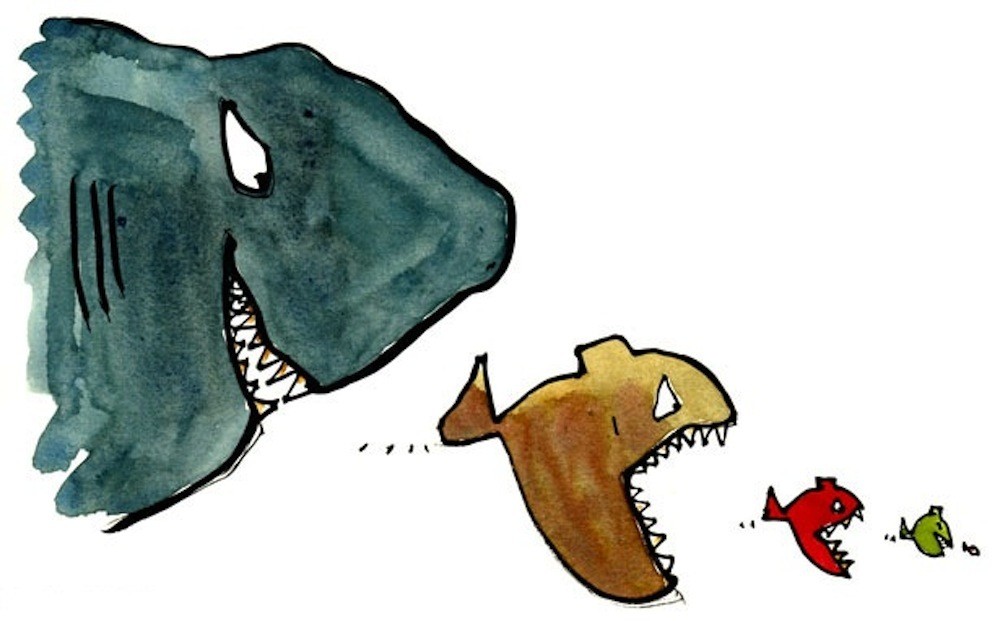

In today’s market, deal professionals can expect lots of questions, a certain amount of conservatism, and even some resistance to acquisitions from their Directors. Communications between the two parties may be further strained by varying degrees of acquisition experience and gaps in M&A knowledge among board members. In short, it can sometimes feel for deal professionals very much like an uphill battle to get a deal approved.

There is no sure-fire recipe for successful interaction with a Board, but I can at least offer some advice on what information they need and some best practices for communicating.

First, let’s address the contents of a standard deal package for Directors. In my experience, there are five principal pieces of deal information that a Board needs and asks for from its Corporate Development staff (roughly in order of importance):

- Deal Rationale: As a corporate development professional presenting to a BOD, you should always lead with your deal rationale, including relevant info regarding valuation, management, strategy, products/services, market size, etc. You should describe your deal in the most concise and cogent manner possible. In plain English, you’re trying to answer, “Why should we do this?” Please re-confirm all the points of your deal hypothesis each and every time you bring the Board up to date.

- Financial Impact Analysis: The near term financial impact of any proposed acquisition will be foremost on the Board’s mind as it listens and evaluates. Here, you must provide just one thing to address the Board’s needs: an accretion analysis. Recall that Directors are notoriously myopic, and near term financial impact will probably be the single most important, and sometimes the only, factor in determining whether your acquisition will go forward or not. Sorry, but that’s life.

- Process/Timeline Update: You should comment directly on the deal process and anticipated timeline for completing the acquisition. Buying a company is a large, complicated project, and project management of key corporate affairs happens to also be a duty of the Board. Timing is a major deal consideration for the BOD; don’t under estimate its importance.

- Due Diligence Update: You should provide an update on due diligence. Make it brief if there are no issues, but be sure to mention anything material that has popped up during your inquiries (it’s your duty to keep them informed) and link your comments to details about potential impediments to closing (see above, Timeline).

- Alternatives: Lastly, and very importantly, you should always provide a couple alternatives to your proposed transaction. “Huh?!?”, you might say. “But why…?” Well, in a nutshell, in corporate development your job is to provide a way to get from point “A” to point “B” via outside (inorganic) means. You must furnish several viable paths to strategic success; everything can’t be riding on one deal or one strategy. Lots of people forget to do this, but by showing the Board several different potential approaches and solutions, you are actually both doing yourself a favor and helping the Board meet its fiduciary duty of care responsibilities.

So those are the key pieces of information the BOD needs…but any deal professional will tell you that the manner in which deal information is conveyed is awfully important too. Here is my advice on how to effectively communicate with your Directors:

- Strive for Consistency: As previously discussed elsewhere in this blog, you should strive for consistency not just in the information you provide to the Board, but throughout your entire strategic acquisition program. From initial target screening all the way to negotiation and closing, consistency is the clearest predictor and hallmark of corporate development success. Be organized and consistent in every element of your deal program.

- Stay within Established Parameters: Also as previously mentioned elsewhere in this blog, you should establish acceptable/permitted financial parameters for acquisitions with your Board (i.e., revenue, geography, EBITDA multiples, employees, etc.). You have pre-negotiated parameters for your acquisitions, haven’t you? Let’s face it — your job is easier when you propose targets that are a pre-approved fit.

- Simplify, Simplify, Simplify: In all cases where numbers are needed, you should provide high level, much-simplified financial models and analyses to help the Board quickly grasp your point without getting lost in the details. Provide only the big-picture model or analysis, but make sure to mention that full details are available for those desiring more information.

- Provide Key Assumptions: Yes, I’ve advised simplifying models and analyses above, but that doesn’t absolve you from responsibility for explaining the key assumptions you’ve made running those high level numbers. Include all the relevant assumptions as well as the facts supporting those assumptions.

Market conditions have intensified pressure on BODs, and they are more fully engaged and hands-on in managing enterprise risks, including those in and around strategic M&A. At the same time, however, Directors understand that deal making drives earnings growth and that acquisitions are increasingly necessary in this slow economy. As a deal professional, you can help your Board manage these disparate duties by understanding their information needs and communicating accordingly.

Posted by: Mory Watkins

So, in a nutshell, what are the keys to successful corporate mergers and acquisitions? What follows is my guidance and my opinions taken from a career full of M&A deals. This is practical, time-tested advice for executives desiring to grow their companies via acquisition.

So, in a nutshell, what are the keys to successful corporate mergers and acquisitions? What follows is my guidance and my opinions taken from a career full of M&A deals. This is practical, time-tested advice for executives desiring to grow their companies via acquisition.