Did you know that now there are only about half as many publicly traded companies as there were in 2000? I didn’t.

The number of publicly traded companies always ebbs and flows, but the current number has fallen steadily since 2000. At 3,678, the number of companies available for the public to invest in is much closer to the all time low of 3,069 in February 1971 than to the all time high of 7,562 in July 1998. Granted, there are thousands of stocks traded on “Pink Sheets” and other lightly or unregulated markets, but the Wilshire 5000, which only includes those that trade on an exchange such as the New York Stock Exchange or Nasdaq, can’t even maintain enough companies to reach its namesake number of 5,000. There are now only 3,678 companies in the index, which is down by more than a third in a decade, and off by nearly half from its level in 2000.

But it’s not just a blip with the Wilshire 5000. The total number of listed securities trading on the Nasdaq OMX and NYSE Euronext exchanges was 4,916, according to the World Federation of Exchanges. The number of listed securities on these two critical exchanges has fallen every year since 2009 and is down 32% since 2000 and 39% from the recent peak in 1997.

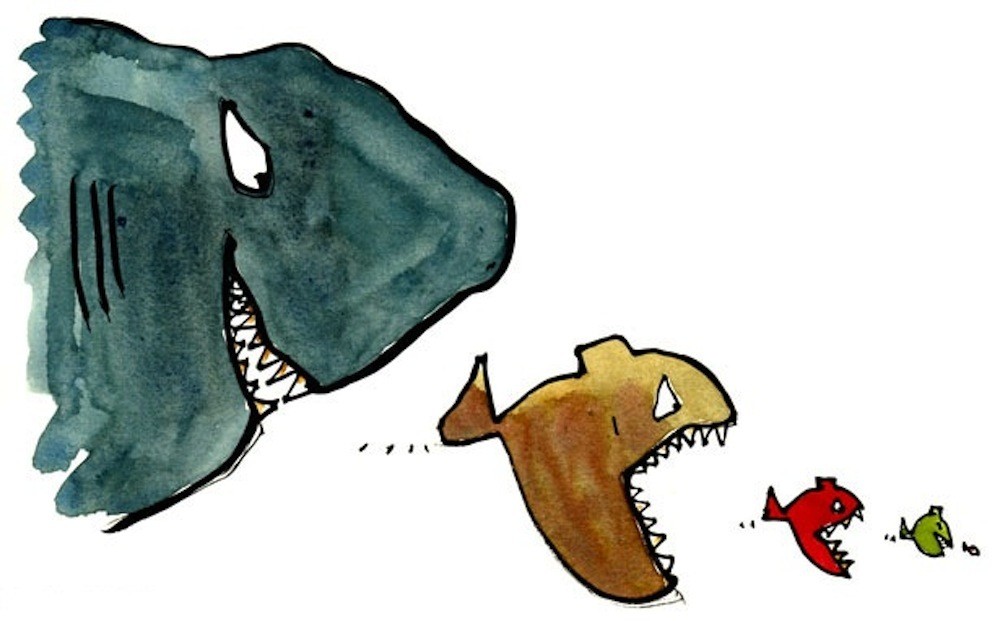

Why is this? One of the main reasons cited is that corporate acquisitions have eliminated and absorbed scores upon scores of candidate companies. Even during the recession years of 2008 and 2009, 8,778 and 7,415 U.S. companies, respectively, were bought. Those figures have steadily increased to 10,108, 10,518 and 12,194 in 2010, 2011 and 2012, respectively, due to a combination of cheap acquisition debt and relatively lower acquisition multiples during the last three years.

Other hypotheses include the increasing expense/hassle of being public, the prevalence and domination of larger public companies, investor distrust of stocks, and involuntary delisting. There is little new supply of public companies either, of course, as the initial public offering market remains moribund.

No one can say for certain exactly why the number of tradable equities has fallen so precipitously, but the trend for fewer rather than more public companies should continue for the foreseeable future.

Posted by: Mory Watkins; excerpted, in part, from an article recently written by financial reporter Matt Krantz.

Today, a brief posting about shortcuts and practical rules of thumb for figuring out whether a prospective transaction might be accretive or not.

Today, a brief posting about shortcuts and practical rules of thumb for figuring out whether a prospective transaction might be accretive or not.